CDO Meltdown (3): Summary of Results

(Part 1, 2)

My previous post summarized a few major aspects of that were well-known about CDOs--mostly notes from the first 27 pages of Anna Katherine Barnett-Hart's thesis, "The Story of the CDO Market Meltdown." However, this is just the first quarter of a 115 pp. paper. What follows is attempt to summarize more of the actual findings peculiar to the paper.

EXAMINATION OF THE CREDIT RATING AGENCIES

The credit rating agencies (CRAs) consist of Moody's, Standard & Poor's, and Fitch. Fitch was a relatively minor player in the CDO sector for reasons that will be investigated in the "Findings" part of this post. Letter ratings by the CRAs have had statutory significance for decades, since pension funds were required by law to invest only in AAA securities.1 In theory, institutional investors or banks were obligated to practice due diligence; complete abdication of responsibility to CRAs for such an important function seems rather extraordinary.

The ratings supplied by CRAs are supposed to measure the likelihood of fulfillment of the obligations of the underlying security. The securities we are talking about are securitized debt and bonds, or derivatives thereof, and the question that a rating is supposed to answer is, How likely is it that the investor will receive principal and interest on time? In some cases, interest payments and principal are rated separately; in other cases, the only thing being rated is the likelihood of the of the investor getting the initial investment back.2

After 2002, when the CDO became a major investment vehicle, CRA business soared.3 A curious aspect of this boom in ratings demand was that CRAs were now the most important customers for their own product. CRAs rated residential mortgage backed securities (RMBS) or other constituents of CDOs, and then used these same ratings (plus formulae for pooling and diversifying risk) . For purposes of pooling, it was useful to have multiple CRAs rate the same security, and then use it in multiple CDOs. If a CRA was assessing securities already rated by another agency, it would typically "notch" the rating (downgrade it one grade).4 So "duplication of effort" was a major source of business.

Of course, "duplication of effort" did not occur as far as due diligence was concerned. Instead, a few data inputs were used to assess the base assets. Ratings did not correlate well with rates of default or with subsequent downgrades, even by the limited metrics imposed by the agencies themselves. But CDOs were supposed to incorporate the broader, systemic risk of loss; this, the CRAs were unable to do.5

In the event, the CRAs' own staffs were never able to agree on a single coherent notion of what risk was.

EXAMINATION OF THE UNDERWRITERS

The underwriters were investment banks that created CDOs . By far the largest ABS CDO underwriter was Merrill Lynch, followed at a distance by Citigroup.6 Soon the underwriters ran out of asset-backed securities and began to incorporate assets consisting of tranches from earlier CDOs. Merrill Lynch, for example, bought 32% of its own RMBS and CDO issues for CDO repackaging.7

Underwriters made the situation worse by carrying the super-senior tranches in off-book special purpose vehicles (SPVs) , justified to regulators by hedging--i.e., purchases of credit default swaps (CDS). Merrill Lynch was thus obligated to write down USD 51.2 billion in the wake of the crisis.8

However, there was immense difference in performance of CDOs depending on the originator. Goldman Sachs performed comparatively well, with "only" 10% default compared to 40% for JP Morgan.

Hypotheses

Barnett-Hart lists several hypotheses she tests using a combination of regression analysis and probit analysis (p.36).

- Hypothesis 1A ("The Housing Effect"): Increasing exposure to residential mortgages, specifically subprime and Alt-A RMBS, is associated with worse CDO performance as measured by defaults.

- Hypothesis 1B ("The Vintage Effect"): Increasing exposure to 2006 and 2007 vintage collateral, particularly assets with floating interest rates, is associated with worse CDO performance as measured by defaults.

- Hypothesis 1C ("The Complexity Effect"): Increasing the amount of synthetic collateral, the amount of pre-securitized CDO collateral, and the overall number of collateral assets is associated with worse CDO performance as measured by defaults.

- Hypothesis 2A ("The Underwriter Effect"): Holding constant general CDO characteristics, CDO performance varies based on the underwriting bank.

- Hypothesis 2B ("The Size [of the underwriter's CDO business] Effect"): The performance of an underwriter’s CDOs varies according to the size of their CDO business, with overly-aggressive or very inexperienced banks issuing worse CDOs, as measured by their ex-post defaults and rating downgrades.

- Hypothesis 2C ("The Originator [of the underlying collateral] Effect"): Controlling for the type of mortgages issued, as measured by average FICO, CLTV, and DTI scores, the performance of a CDO depends on the specific entities that originated its collateral assets; in other words, was CDO performance affected by the emergence of banks that acted as both CDO underwriters and collateral originators?

- Hypothesis 2D ("The Asymmetric Information Effect"): CDO performance will be affected if it contains collateral originated by its underwriter, although the performance might improve or decline, depending on the importance of reputation vs. adverse selection and moral hazard.

- Hypothesis 3A ("Recycled Ratings Effect"): The most important factor in explaining initial levels of AAA given to a CDO are the credit ratings of their collateral pool.

- Hypothesis 3B ("The Peer Pressure Effect"): The % of AAA given to a CDO will depend on the number of rating agencies rating the deal.

- Hypothesis 3C ("The Seniority Effect"): Controlling for the default rate of the CDO collateral, senior tranches have experienced more severe downgrades.

- Hypothesis 3D ("The Asset-Class Effect"): The realized defaults associated with a given credit grade varies based on the asset type. Similar to Hypothesis 1A, except that here we're interested in the effect on default likelihood for a given CRA rating applied to CMBS versus RMBS or HEL.

- Hypothesis 3E ("The Super-Senior Effect" : Rating agencies were overly optimistic in giving AAA ratings. CDOs given more initial AAA ratings, in terms of number of AAA tranches and percent of the transaction rated AAA, are now exposed to larger losses. The name for this hypothesis was apparently inspired by Janet Tavakoli (2005), in which she cites the impact on the actual risk of a waterfalled security of a super-tranche. CRAs did not specifically account for the additional risk posed to the smaller AAA tranche by having a larger share of the CDO's liabilities be senior to it.

- Hypothesis 3F ("Conflict of Interest"): Conflicts of interest caused by the fee system of credit ratings would result in more aggressive initial ratings, subsequently more downgrades, and worse accuracy in prediction for the CDOs of large underwriters. Barnett-Hart tested this hypothesis by comparing the amount of business the CRAs did with each underwriter with the number of tranche-rating downgrades. A very large downgrade meant a larger favorable bias toward the underwriter, which was (in turn) tested against the volume of business the CRA did for that particular underwriter.

RESULTS OF THE STUDY

About half of the variation in ABS CDO performance was the result of CDO asset and liability properties (Hypotheses 1A-1C). In particular, regressions of asset and liability properties explained almost 60% of the downgrades in ratings for individual tranches of CDOs. The results are summarized on p.91.

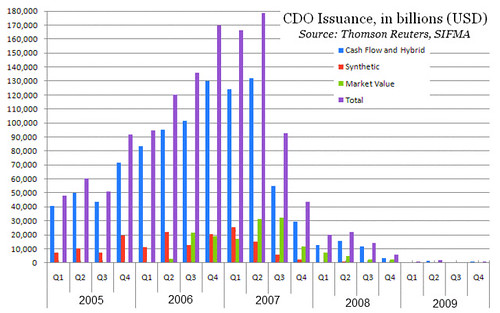

Most hypotheses were validated, although it takes a close reading of the result tables to say how validated each one was. CDOs had a strong likelihood of failing if they were created in 2006-2007, were issued backed mostly by residential mortgage securities (as opposed to commercial mortgages , etc.),9 and were complex.10 This is to be expected; narratives of financial crises should rely on failed business models or regulatory systems. Narratives that "expose" a single person or institution as wickedly inflicting the disaster on a hapless financial system are unsatisfying.

Hypotheses 2A-2D dealt with the underwriter contributions to CDO performance, and explained less of the variance in CDO performance. Nonetheless, they were still interesting to economists. Hypothesis 2A involved a simple ranking of underwriters by CDO performance; effect of [collateral] origination and assymetric information (i.e., hypotheses 2C & 2D) was ambiguous. Some collateral originators performed worse than the rest, but mostly the asset composition was a stronger explanation (2C). Likewise, in some cases it helped that the originator of CDOs was a large player, but aggressiveness in growing structured finance departments was not a good sign (2B); and there was considerable variation from underwriter to underwriter as to the effect on using one's own collateral in a CDO tranche (2D).11 These results arguably suggest that underwriters were eclipsed in importance by the fundamental business model applied to CDOs and the strategic position of the particular underwriters. For example, Goldman Sachs was in a peculiarly advantageous position with respect to the underwriters and was not obligated to pursue CDO business aggressively.

(It needs to be added that table 7 summarizing the ranking of CDO underwriters based on (a) CDO default and (b) CDO tranche rating downgrade yielded entirely different results. Goldman's CDOs had the lowest frequency of default, followed by Lehman; but Goldman was ranked 11th for ratings downgrades.)

The hypotheses 3A through 3F pertained to corruption of CRA ratings per se. Here, the hypotheses behaved very differently indeed from what was expected. While attempting to confirm Hypothesis 3F ("Conflict of Interest"), for example, Barnett-Hart ran up against the problem that the ranking of underwriters by ratings demand was the same for all three CRAs. Moreover, the largest underwriters often were the worst. To make matters more ambiguous, the real problem was that there was too little variation in ratings, not to much. Using jargon from behavioral economics, the problem was signals compression: the difference in real quality of securities, from T-bills to Countrywide CES RMBS was huge, and the ratings ought to have reflected this. Instead, the ratings reflected very small differences across the range of underlying reality.

One regression, for example, ranks underwriters by the accuracy of their ratings (table 14, panel B, p.89). The twist, here, is that the ranking reflect the success of the CRAs to make accurate judgments of the underwriters being ranked. It happens to closely match the ranking of underwriters by performance of CDO (where higher ranking means fewer defaults). In effect, the CRAs were "righter" about the best underwriters, and "wronger" about the worst.

Barnett-Hart concludes:

The errors of the rating agencies stemmed from neither conflicts of interest nor preferential treatment given to certain banks. The true culprit behind the rating agencies’ failure was the outsourcing of credit analysis to computer models and the low level of human input used to rate CDOs (p.94).In a later post I want to address broader conclusions regarding the CDO market meltdown.

(Part4)

Notes

- The term "AAA" is used by Standard & Poor's and Fitch; Moody's uses "Aaa." Here et alibi, "AAA" = "Aaa."

- Tavakoli (2005), p.9; via Barnett-Hart (2009). Barnett-Hart uses the page numbers from the PDF file; here, page numbers are from the issue of the original periodical.

- From exhibit

, Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, April 2010, p.18.

, Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, April 2010, p.18.Moody’s gross revenues from RMBS and CDOs increased from just over $61 million in 2002 to over $208 million in 2006. S&P's net annual revenues from ratings nearly doubled from $517 million in 2002, to $1.16 billion in 2007. During that same period, the structured finance group's revenues tripled from $184 million in 2002, to $561 million in 2007. In 2002, structured finance contributed 36 percent to S&P’s bottom line; in 2007, it contributed 48 percent – nearly half of all S&P revenues. In addition, from 2000 to 2007, operating margins at the CRAs averaged 53 percent, far outpacing companies like Exxon and Microsoft, which had margins of 17 and 36 percent respectively in 2007.

This information added in an update to the original post. - Barnett-Hart (2009), p.20

- Tavakoli (2005), p.10.

One would think that rating agencies would at least be inter- nally consistent. But that isn’t necessarily true. Even within the same rating agency, portfolio tests and restrictions may vary by deal, and some deals are better protected than others. Different structurers within a rating agency may choose different stress scenarios when evaluating cash flows for an ultimate rating.

With respect to the broader measure of systemic risk: " Conventional general market risk to a portfolio is not captured by ratings." (p.9)

[....]

In 2004, Fitch’s model showed such unreliable results for structurers using Fitch’s fre- quently changing correlation matrix that industry observers dubbed it the "Fitch Random Ratings Model." - Barnett-Hart (2009), p.26. Here is the complete list.This table presents the number of ABS CDO deals underwritten by the top 10 underwriters between 2002-2007. The data were obtained from S&P’s CDO Interface.

Underwriter 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 TOTAL Merrill Lynch 0 3 20 22 33 18 107 Citigroup 3 7 13 14 27 14 80 Credit Suisse 10 7 8 9 14 6 64 Goldman Sachs 3 2 6 17 24 7 62 Bear Stearns 5 2 5 13 11 15 60 Wachovia 5 6 9 16 11 5 52 Deutsche Bank 6 3 7 10 16 5 50 UBS 5 2 5 10 16 6 46 Lehman Brothers 3 4 3 6 5 6 35 Bank of America 2 2 4 9 10 2 32 TOTAL DEALS 47 44 101 153 217 135 697 - Ibid., p.27. Repackaging of CDO securities into a new CDO resulted in a "CDO-squared." The Royal Bank of Scotland did this an average of 5.32 x for its CDO securities. Merrill Lynch did it 4.79x. These were extremes, but Merrill Lynch was the biggest underwriter.

- Ibid., p.32. CDS is supposed to be a form of insurance for default (rather than a proper swap), but almost immediately became very popular as a way for non-holders of CDO securities, like John Paulson, to bet against the housing market overall. The counterparties in the CDS transactions received a premium when defaults did not occur, but when they did, suffered enormous losses that required government bailouts to prevent a general run of CDO securities. This was problematic since so much of the money used to bail out the financial system went to pay off speculators like Paulson.

- This hypothesis is somewhat problematic because such a large share of ABS CDOs were based on housing collateral. Remember, this category excludes the larger pool of synthetic CDOs as well as a smaller group of CDOs based on corporate bonds. RBMS accounted for about 14% of all ABS deals in 2006-2007 (Barnett-Hart, p.9, table 2) , but home equity loans (HEL) were more radioactive still and accounted for another 34% of deals during that period. Of the remaining 52%, another 11% were pre-existing CDOs (which incorporated a slightly different share of HEL & RMBS; see next footnote below). Only about 40% of the total were commercial mortgages or "other": credit card debt, car loans, and so on.

- Complexity is measured by the coefficients on Number of Assets, % Synthetic, and % CDO. Please note that CDOs were a non-housing asset and "% synthetic" impinges on the 40% of ABS CDOs that were neither housing nor CDO. As it happens, synthetic CDOs performed relatively better than ABS CDOs--they failed at about a fifth the rate of ABS CDOs (See Part 2, Ftnt 4 & 5).

- For a description of the findings:

- Hypothesis 2A, p. 56 & table 7 (p.63, panel A);

- 2B p.57 & table 7 (p.64, panels B.1 & B.2)

- 2C: p.58 & table 8 (p.63)

- 2D: p.59 & table 8 (p.65)

*

Sources & Additional Reading

Efraim Benmelech & Jennifer Dlugosz, "The Credit Rating Crisis"

Anna Katherine Barnett-Hart, "The Story of the CDO Market Meltdown: an Empirical Analysis"

Janet Tavakoli, "Structured Finance: Rating the Rating Agencies "

Dr. Michael Wang, Shwn Meei Lee, & Dr. John Ku, "Risks and Risk Management of Collateralized Debt Obligations"

Yves Smith, "The Role of CDOs in Merrill’s Losses (Updated and Expanded Version)," Naked Capitalism (24 October 2007)

Global CDO Issuance, SIFMA (Excel spreadsheet). Outstanding source on CDO statistics.

Labels: economics, finance, regulation, structured finance

Labels: economics, finance, regulation, structured finance