CDO Meltdown (1)

By now, the collateralized debt obligation is surely a household word. The technical nuances of CDOs remain obscure, but the essential problem here was that financial engineers believed that, by using past data they could quantify risk of default, and then pool that risk. Pooling risk, under certain circumstances--explained below--reduces risk to manageable levels.

Those circumstances include two crucial conditions: the risk being pooled must absolutely have zero correlation. Very small correlation is all right--it's not the "zeroness" that's important, it's the certitude that it is low under all circumstances. The other condition, which is really just a reiteration of the first, is that the actions of the financial engineer must assuredly have no impact whatever on the risk itself.

The first condition, in other words, means that an event that affects all the things at risk (e.g., an earthquake hitting a large ratio of properties insured by a particular firm) must never happen. The second condition means that the act of creating an insurance pool, or financial instrument, can never actually influence the risk of the parties themselves (taken as individuals). If the invention of insurance sharply alters the behavior of the insured, then actuarial data is inherently inaccurate.1

As is now well established, the CDO made credit extremely cheap. This was done by producing an estimate of risk that could be prepackaged into a tradeable security, bundled using a structured investment vehicle (SIV), and sold with a mathematically-inferred projection of return. While credit extended to high-risk borrowers has a high probability of default, this probability was supposedly offset by pooling (with other, lower-risk borrowers) to achieve a suitable investment-grade bond.

THE CDO: A SHORT DESCRIPTION

A collateralized debt obligation (CDO) is a type of structured finance product, in which the originator creates an entity like a special purpose vehicle (SIV) to own loans and distribute payments on certificates. The CDO represents a claim many different potential kinds of assets:

- investment grade and high-yield corporate bonds;

- emerging market bonds;

- residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS);

- commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS);

- real-estate investment trusts (REIT) debt;

- bank loans;

- special-situation loans and distressed debt.

CDOs are generally classified as "cash" or "synthetic." A cash CDO consists of a pool of bonds or loans. Their asset value is tied to the cash flow of the underlying assets, which consists of payments on the principle and interest.

Synthetic CDOs sell credit protection via credit default swaps (CDS) rather than debt-based assets. The CDO's asset value is pegged to specific tradeable assets, but it emulates the capital gains of the assets with derivatives (rather than ownership); hence, it is more highly leveraged. The collateral comes from a cash deposit by the depositor/investor.

The CDO pays out returns at maturity to investors at different levels of priority. In the event that there is widespread default, some of the tranches are guaranteed first, second, or third priority of repayment. The highest-risk [equity] tranches, with a high nominal rate of return, take any hits in the event of default. This is called a "waterfall structure."

CDO asset pools were quite large; typically, they involved nominal values of about USD 500 million to >USD 5 billion.4

RATINGS

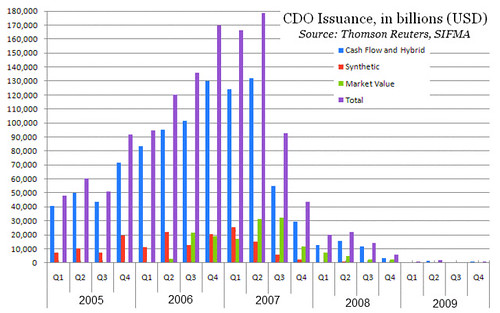

Click for larger image |

There was an obvious conflict of interest in this arrangement, but structured finance and tranching made it worse. That's because the ratings for CDO issues were extremely important to the creation of a shadow banking system, in which liabilities could be parked off bank balance sheets, without the usual reserves or capital adequacy; and because ratings were so important to the design of CDOs.

Because of what a CDO is, it requires the ratings agencies to collude in the design and ultimate strategy of CDO-style structured finance. The tranches are rated separately; in theory, the superior senior tranch of 2006-vintage synthetic CDOs were actually better than AAA, since they had AAA-assets as collateral.5

COLLATERALIZATION

A critical part of the narrative was collateralization. A debenture is a debt instrument (like a bond) that is not backed by any collateral. Most bonds are debentures; CDOs supposedly would be safer than debentures because the creditors could, in the event of default, auction off the collateral. As we now understand, this collateralization was to allow the crisis to spill over more readily into the real economy.6 This was because CDOs created a bubble in housing prices (millions of people could borrow more than before, and bid up the price of housing--see Warren & Tyagi, 2004)

The effect of collateralization was most obviously to create not only a huge gap between the bubble price and the bust price of houses; it also flooded the rest of the credit markets with loanable funds for consumption. Arguably, this is a strategy that is not readily available for economies whose currency is not the universal reserve currency. That's because rapid expansion of the money supply is liable to lead to capital flight (interest rates fall below a competitive level). But it has a disproportionate effect on consumption, since entrepreneurs are guided by other considerations besides cheap loanable funds. This may explain why the US has such a large and persistent trade surplus. In any event, the CDO meltdown has led policymakers to wonder how the financial system could remain both innovative and stable.

(Part 2)

Notes

- There is evidence it has a modest impact on the insured, but over time this impact has been statistically neutralized. See my post on "The Curmudgeon's Fallacy." Actuarial data, whether for insurance companies or financial instruments, seeks a stable estimate of risk so that the potential for loss is accurately priced. If the methods of assessing loss potential produce results that change frequently over time, then those methods are not useful for managing the probable costs of loss.

- List of assets from Fabozzi, Davis, & Choudhry (2006), p.119

- For a summary of the "parallel banking system," see Tobias Adrian & Hyun Song Shin, "The Shadow Banking System: Implications for Financial Regulation"

, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 382 (July 2009)

, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 382 (July 2009) - The largest CDO I was able to locate was MAX 2008-1 A1, with a notional value of USD 5.4 billion; it was underwritten by Deutsche Bank, which retained 94% equity in it. See Yves Smith, "Debunking Some AIG/Fed/CDO Theories," Naked Capitalism (4 Feb 2010). Smith cites disclosures of Maiden Lane III LLC transactions by Federal Reserve.

- "A 'Rational' Explanation of the Financial Crisis" Macroeconomic Resilience (November 2009)

- The real economy is distinguished from the financial sector. Usually there is some insulation between the real economy of goods and services, and the "not-so-real" economy of stocks and derivatives.

Additional Reading

Anna Katherine Barnett-Hart, "The Story of the CDO Market Meltdown: an Empirical Analysis"

Frank J. Fabozzi, Henry A. Davis, & Moorad Choudhry, Introduction to Structured Finance, John Wiley and Sons (2006)

Michael S. Gibson, "Understanding the Risk of Synthetic CDOs"

Elizabeth Warren & Amelia Warren Tyagi, The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle Class Parents are Going Broke, Basic Books (2004). This book provides an invaluable explanation of how financial institutions and the two-income family combined to create a bidding war for houses in attractive neighborhoods. Warren & Tyagi wrote before the 2008 Financial Crisis but described a growing emergency in household finance that had burgeoned during the 1990's.

Credit Write-downs: Creditflux's list of credit write-downs announced since the start of the subprime crisis. Creditflux write-downs (Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet, 78 kb)

"Global Cash Flow and Synthetic CDO Criteria"

Labels: economics, finance, regulation, structured finance

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home