Ecological redemption is where land and water are "recovered" for industry; for example, if a forest is felled and tilled, and the water in the creek captured for irrigation. In areas outside or on the peripheries of the

TEP, some or most of the population is either IN THE WAY OF, or THE TARGET OF, or A POTENTIAL RESOURCE IN, the process of ecological redemption.

Imperialism begins for several reasons, but usually develops into a campaign of ecological redemption. One of the more obvious examples is the transformation of the Caribbean and Southeastern USA from high density forests into a zone of high density cultivation. This is the subject of a fairly important book entitled

Late Victorian Holocausts (Michael Davis, 2001; link is to review by Amartya Sen), which assembles research by several scholars on the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) system and its early manifestations. According to Davis, et al., the ENSO's effect on the global as a recurring natural disaster began with both the civil pandaemonium of high imperialism and the ecological impact of mass territorial transformation. The cultivation of huge new regions of North America for wheat, for example, altered weather patterns of the Northern Hemisphere in ways that no one could possibly have predicted. The affect, having occurred, became a permanent feature of the climate zones that I'll bring up again in a moment.

The impact of civil violence (imperial conquest, liquidation of the political system with its imbedded social structures, and establishment of a rival economy) is described by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen:

The distinction between the effects on overall food supply and those on family incomes is important in explaining why some people are so severely affected by a natural disaster whereas others -- living in the same society and facing the same supply of food -- are hardly touched at all. It helps explain, too, why famines cannot be averted simply by opening up markets, or by making transportation easier (for example through the establishment of railways), so that food can physically be moved to the affected people. Davis rightly presses the question: ''How do we weigh smug claims about the life-saving benefits of steam transportation and modern grain markets when so many millions, especially in British India, died alongside railroad tracks or on the steps of grain depots?''

The problem lies in the fact that disaster victims do not have the means to buy the food that the market can deliver and the railways can fetch. Indeed, sometimes the very opposite happens, as when food is moved out of the famished area, pulled by the greater purchasing power of more prosperous regions (well illustrated, for example, by the persistent shipment of food from starving Ireland to affluent England during the Irish famines of the 1840's). It is, therefore, a mistake -- common though it is -- to expect an automatic solution to famines and hunger through the development of markets and the establishment of transport arrangements. This effect, I think, was understood by "the man on the spot," although what I find very disturbing from the contemporary accounts of colonists was the same sense of expanding into a terra nullus emptied of occupants. Conquering a territory occurred in phases, with progressively more intensive control over a territory; settling, hiring labor (or enslaving it, and importing it), and exporting produce were usually carried out by people who came from different, even alien and hostile, walks of life. To the natives, likewise, the experience was varied depending on who encountered which phase. So imperialism, rather than being a single, massively parallel, act of individual cruelty, was instead a conveyor of quiet intimidation or manipulation of "Whites" as well as more obvious victims.

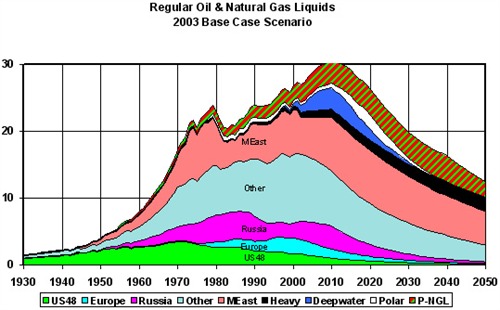

The second part, the massive alteration in the flow of water through a landscape, or the cultivation of alien species in it, was of course, the real impact humans have had on the planet; it was also the most lasting and potentially dangerous effect of imperialism. Our planet is governed by cycles, such as in the levels of CO2 in the air, or the interaction of ocean currents with air currents. These can sometimes lead to catastrophes, of course; but like any system, these cycles

tend towards stable, harmonic repetition. However, these cycles can sometimes be so influenced that they are changed into a new rhythm. Simple examples include the spring that is pulled so far that the metal is bent, and thereafter has a different oscillation rate when it is released, than before it was bent; or the balance between predator and prey in a habitat, where the wolves eventually become so numerous they reduce the rabbits to an evolutionary bottleneck; the rabbit population, which has had peaks and valleys for centuries, now cannot recover to its former level because this one time it was pushed too close to extinction. These are examples of hysteresis.

Hysteresis in the environment is common, and in the example of the wolves and rabbits, can occur without human intervention. However, it is a potentially massive force in the climate and understanding the risks of human hysteresis is both demanded by ecological redemption, and made possible by it. After it happens, the cycles continue, but at either a different applitude or frequency. This is the ultimate bad of imperialism, and yet the crucial matter to understand about it is that imperialism is a system and an event that the system inflicts. It is recurring. It continues, and it transcends the interests and the very existence of the imperial power. And its main impact is a new climate, with new landscapes and new resident populations.

Those in the way of the project of ecological redemption have at sundry times been exterminated, either by dispossession (as, for example, the Indians of North America) or systematically rounded up and massacred, as Darwin described in The Voyage of the Beagle.

1 Examples of these are quite numerous. Those who were a target of the TEP include, again, the Indians of North America: after the War,

Lt. General John DeWitt (who had earlier organized the relocation and internment of Japanese to concentration camps), organized the relococation of American Indians to urban areas.

2On the other hand, there are peoples who are targets of the TEP; they are to be transformed into industrial workers and consumers. Readers will either be skeptical of (or hostile to) my distinction between "in the way" and "a target of"; the latter implies that the Europeans, confronted with an "inert" Native population, sought to transform them as if they were a passive resource. Partly this was to resolve the sins of the past, which could not reversed; partly it reflected normative goals of democratic capitalism, in which economic inertia is unacceptable:

In a proposal for the new relocation services, Kent Fitzgerald outlines the economic need for relocation; he asserts that the growing Indian population can no longer be supported by the reservation economy. In The Relocation of Indian People away from Indian Reservations, ... he writes about the Winnebago tribe in Wisconsin which does not have a reservation but whose community is scattered throughout twenty counties across the state. He notes that in this particular instance “this procedure, which had as its purpose keeping the members of the tribe apart and forcing them to associate to a larger extent with their White neighbors has had no such effect. They are still a distinct group and are ekeing out a miserable existence in rural slums which should be a source of shame to both the Federal Government and the State of Wisconsin.”

[Op. cit., p.33-34]

Altering this was a matter of national honor and the legitimacy of the republic. I must hasten to add that the bourgeois and Communist governments of Central Europe republics likewise wrestled with the surviving Roma population, seldom with success.

3North American and Europe have minorities who are "targets," such as certain cohorts of the African American community, or les beurs of France (or the Roma everywhere). However, outside of the project of ecological redemption, we often encounter elites who are entirely preoccupied with the transformation of their societies into industrial workers (most spectacularly, Communist countries

4). The early years of

the Saudi monarchylikewise featured an attempt to transform the population into a sort of Sparta.

There were also societies whose populations were a potential resource in colonialism: most obviously, Africa, with the transatlantic slave trade, but after 1834, also China and India (with the trade in indentured labor).

Finally, there are countries whose populations have been easily sidestepped or ignored by colonialism. These are outside it and only recently have come under significant pressure to transform their societies in conformity to the colonial endeavor. These are, of course, areas that are difficult to reach.

(

Cross-posted at Hobson's Choice)

NOTES:

1 The place was Patagonia; the perpetrator was General Manual Rosas, who was ousted in 1852 and moved to England.

2 The one source on this subject is "

The Spatial Dispersion of Native Americans in Urban Areas: Why Native Americans Diverge from Traditional Ethnic Patterns of Clustering and Segregation" (PDF; rightclick and select "download link," then open in Acrobat), Shannon Louise Roberts, May 2004; doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, NY, NY. When I write "

Op. cit.," this is the opus.

Caveat: Ms. Roberts recommends

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, by Dee Brown. The subject matter in this book is far more successfully treated in

The Patriot Chiefs: a Chronicle of American Indian Resistance (Alvin Josephy, Jr., 1958);

The Long Death (Ralph Andrist, 1964);

The Roots of Dependency (Richard White, 1983; for a sociological-economic perspective). Dee Brown's book set back the field several decades.

3 Isabella Fonseca,

Bury Me Standing. References are distributed throughout the book.

4 Edward H Carr,

Foundations of a Planned Economy or

The Interregnum.

Labels: economics, environment, semantics