The Gold Standard-2

Part 1

In part 1 I briefly outlined the periods of gold standards and gold exchange standards.

Oddly, the concept became significant with the introduction of paper money, since pure commodity money had entirely different dynamics. In fact, the period of commodity money naturally begat the widespread use of bimetallism, since many of the world's financial systems prior to 1800 had evolved out of coins with different alloys and constituent metals. The masters of the royal mint were typically concerned with maintaining a fairly high local price of gold and silver, the one so that private reserves of gold would accumulate domestically, the other so that there was an ample supply of small denomination coins for daily use.

Braudel (1992, p.357) suggests that the connection between a trade surplus and inflows of gold were discovered after Gresham ("Gresham's Law" being roughly dated 1558). The discovery that a strong currency could be used to strengthen the revenues of the kingdom produced a strong incentive by princes to focus very narrowly on foreign/trade policy that favored trade surpluses and offset Gresham's law.1

The period of pure commodity money seems to have been accompanied by wars explicitly over access to markets and resources. Explaining the frenzy of pre-ideological wars of the 15th-18th centuries is otherwise fairly difficult. After the French Revolutionary wars of 1792-1815, major conflicts within Europe became rare and ideological; balances of power were no longer invoked by diplomats trying to form coalitions.2 While British state expenditures had grown very fast prior to and during the Revolutionary epoch, they fell from about 23% of gross product (1810) to about 8% (1890); there followed an arms race in Europe that drove British state expenditures to 14% (1900) and then to historic highs after 1929.3

The British experience was not sharply different from other European nations, although Germany and the USA had the bulk of their government expenditures at the local level until the early 20th century. Also, there was the extremely important financial role of the colonies (India, Latin America), which had—or were compelled to have—extreme "hard" moneys. In the 19th century, these countries tended to mop up extra liquidity in the system, and internationalized the generally high real interest rates.

The gold exchange standard of the interwar years was extremely unstable. Within literally months of returning to the gold standard, many governments introduced "gold devices" to suppress the bleeding of gold from state reserves. For example, the government of Canada prevented sales of gold by permitting them only in Ottawa, rather than in the financial centers of Montreal or Toronto, and effectively left the standard in 1929 (Powell, 2005, Ch.7 --PDF). The last major countries to leave the gold standard were Italy (1934) and France (1936).4

The postwar period 1946-1971 has some aspects of a GXS; the US dollar was pegged to gold, and the US government had treaty obligations to defend that value through sales of gold. Other national currencies were pegged to the dollar; usually these pegs were determined under pressure of the IMF. Generally speaking, changes in valuation of non-US currencies under the Bretton Woods Agreement were made under negotiation with the IMF, and the IMF was usually interested in getting a stand-by agreement repaid reliably. This, of course, meant erring on the side of a low effective exchange rate for the currency, and thereby ensuring the country's current account balance would improve against that of the USA. It also meant the terms of trade would worsen for that country.

An effect of this was that, in the 1960's, the US dollar came under inflationary pressure. Because the US guaranteed the value of the dollar against gold, and this guarantee was taken seriously, the effect was to push the value of gold relative to all other things downward (not enough; US gold reserves shrank anyway, as trades continued to exchange dollars for gold). Other countries therefore complained that the USA was "exporting inflation" through the use of the dollar as their reserve currency.5 The problem was that the US was obligated to run a deficit in the balance of payments in order to accommodate expansion of the global economy. This was because foreign holdings of US dollars (plus gold, which was not in adequate supply) were needed as reserves if a country was to expand its money supply, which of course was necessary for economic expansion. This meant the US economy had to consume beyond its means, or the world economy would deflate.

|

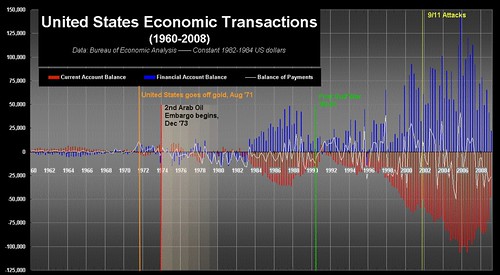

Click for larger image Blue bars indicate inflation-adjusted net influx of foreign investment to US (financial account balance); red bars indicate current account balance. The red and blue bars are nearly mirror images of the other. The white line indicates the difference between the two. Note the sharp rise in imbalances following the collapse of Bretton Woods (15 August 1971) . It's possible the Triffin Dilemma may have continued to operate long after that time, as the linked article explains. |

European critics of this tended to demand a return to a pure gold standard, which would require massive monetary contraction by the US government (and depression). US persistence in the Bretton Woods Agreement would likewise respond to the 1970's Oil Embargo by imposing a recession sufficient to disinflate, but leave intact the European complaint that they were unwilling lenders to Washington. In the event, money was allowed to float in a chaotic fashion, rather like an immense raft hitting a rapid. Weaker, and newer, currencies of the world (e.g., Brazil's, Sri Lanka's) were subjected to devastating shocks, but probably would have fared worse under either BW or the pure gold standard. That's because defending their own peg to gold—if they had one—would have been prohibitive and ultimately impossible, and only added to the debt burden they faced in 1980-86. And without the income from post-BW exports, such countries would likewise have had no way to rebuild sovereign credit.

Internal Effects of the Gold Standard

The gold standard was a technical improvement over either prior forms of paper money or over specie. While the term "fiat money" was apparently first used as an insult, the fact was that states were not always able to exchange even their coins for the par value in gold or silver, and therefore long relied on quite rigorous laws enforcing its use as legal tender. The ability of the state to "will" value into existence, therefore, was used with metal coins for centuries before the French Revolution. True "fiat money," though, requires that the actual purchasing power of the money be also fixed by the state: hence, the money must be inconvertible into other potential monies, such as gold or foreign currency. This is, naturally, quite rare; there are a few cases, such as the use of assignats in France during the Revolution, the Soviet ruble, and so on. More commonly, however, alternative monies are just very difficult to use. Ironically, therefore, the gold standard represented a new technology for defending paper money, one that had been unavailable to earlier forms of quasi-fiat money.

As mentioned in footnote 1, when rival moneys circulated ad libitum in the same country (during, say, periods of free banking), Gresham's Law did not apply: bad money was, in fact, likely to be driven out by good, rather than vice versa. But if that were so, it was not immediately obvious why gold was at all valuable as a reserve. Banks were vulnerable mainly to illiquidity, rather than insolvency, which was what "conservative" management methods were supposed to prevent; and extremely well-managed banks, in effect, drove out gold (whose power in the inter-regional economy of 19th century USA was concentrated by history, not by shrewdness or prudence.) They did this through anti-competitive measures, such as teaming up with other larger banks and threatening weaker, local banks with runs (usually around harvest time, when demand for cash was brisk). Eventually, notes of issue from a small number of large state-chartered banks became required as reserves, instead of specie.

The gold standard, finally, played a major role in the history of panics and "crises" during the 19th century. This is not necessarily an indictment of the GXS, incidentally; the financial system had to evolve out of something, and it's reasonable to argue that the GXS was the most feasible option of the day. But it was not remotely trouble-free. National governments played a massive role in their countries' financial life by maintaining, or failing to maintain, adequate liquidity. Gold strikes typically led to unsustainable booms in credit and economic expansion, while declines in gold output--or major wars--led to irrational contractions in economic activity. This was globalization avant la lettre, and it intruded into every hamlet and tenement of the world.

(Part 3)

Notes

- Link goes to George Selgin, "Gresham's Law," EH.Net Encyclopedia (9 June 2003). Note there was some controversy over what Gresham's Law actually says. Per Selgin, Gresham's Law applies to cases in which coins have their value fixed by state fiat, regardless of the metallic content; therefore, in cases where the coin is not legal tender, and where they may circulate well below par value, Gresham's Law does not apply.

Gresham's Law can hold, on the other hand, where both good and bad coins enjoy similar legal-tender status and where non-trivial sanctions can be applied to persons who insist upon discriminating against bad coin and in favor of good coin. In such cases all coins must be accepted by tale, and the employment of bad coin becomes a dominant strategy in what amounts to a "Prisoners' Dilemma" game in which both sellers and buyers participate. Buyers, knowing that sellers must accept either good and bad coins at their official face value, offer inferior coins, while hoarding, exporting, or reducing better ones; sellers, anticipating buyers' dominant strategy, price their wares accordingly.

The significance was that a government could not attempt to control exports of gold by debasing its currency, and it could not do it by developing an exceptionally strong currency. (In theory, a very dependably excellent currency would eventually pay for itself in increased seigniorage, but getting there would ruin law-abiding citizens holding bad coins at par). In the event, Elizabeth I did devalue ("decry") bad shillings, and this did create severe economic hardship for those who had heretofore obeyed English tender laws. The effect was to "harden" the pound, since there were now fewer pounds in circulation, but the recession more than offset this.

"Offsetting Gresham's Law" refers to the inexorable increase in bimetallic fiat money in the expanding economies of Europe, 1600-1800. In such countries, the ratio of the lower-valued coins to higher ones was fixed by royal prerogative; but lower-valued coins were usually silver, whose value was [usually] declining relative to gold. This created a tension between the expanding demand for money and the state's strategic need for expanding gold reerves, which could only be expanded by an aggressive trade policy. - The major military events in Europe were in 1832 (Anglo-Russian support of Greek struggle for independence; see Frank Smitha), 1848 (conservative reactions; see James Chastain's site), 1852-54 (Crimean War, preserving Ottoman Turkey; see Victorian Web introduction), the Risorgimento or Unification of Italy (Robert Avery, Victorian Web), and the series of German wars 1864-1870 (see "The Process of Unification," Professor Gerhard Rempel, Western New England College).

- Roger Middleton, Government versus the market: the growth of the public sector, economic management, and British economic performance c. 1890-1979, Edward Elgar Publishing (1996), p.90-91, cited in Martin Daunton, Trusting Leviathan: The Politics of Taxation in Britain, 1799-1914, Cambridge University Press (2007), p.40.

- Marc Flandreau, Carl-Ludwig Holtfrerich, & Harold James, International financial history in the twentieth century: system and anarchy Cambridge University Press (2003), p.95ff. Prior to being corrected (20 Oct 2010), this paragraph alleged that France "defaulted on its sovereign debt." This was an error for which I apologize. France has not defaulted on its debt since the Revolutionary Epoch, a fact noted by Carmen M. Reinhart & Kenneth Rogoff in This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Princeton University Press (2009), p.88.

- For example, President Charles de Gaulle of France leveled this allegation in 1965.

In 1965, de Gaulle also attacked U.S. monetary policy. The American deficits, he charged, were exporting inflation to Europe, In his celebrated press conference that dealt with the monetary question, held on February 4, de Gaulle attacked the whole currency reserve system. By permitting endless American deficits, he argued, the system was unsound as well as unfair... Under the gold exchange standard, American deficits that other countries were expected to hold made those countries, in effect, America's unwilling creditors. This involuntary extension of credit coincided with heavy American direct investment abroad. Certain countries were thus experiencing... take-overs that they were themselves financing by holding the surplus dollars.

Robert O. Paxton, Nicholas Wahl, De Gaulle and the United States, Berg Publishers (1994), p.242-243. De Gaulle was advised by Jacques Rueff, an enthusiast of the strict gold standard. Point made in blue typeface was basic premise of Jean-Jacques Servain-Schreiber, Le Defi Americain (1968); ironically, Rueff and Servain-Schreiber represented opposite sides of the political continuum in France. See also Brian Reading, "International Monetary Instability since 1968" (PDF), Lombard Street Research (Nov 2008).

Sources & Additional Reading

Fernand Braudel (Siân Reynolds, translator), Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century: The perspective of the world, University of California Press (1992)

Sam Y. Cross, All About... The Foreign Exchange Market in the United States, Federal Reserve Bank of New York (1998), "Chapter 10: Evolution of the International Monetary System" (PDF)

James Laurence Laughlin, The history of bimetallism in the United States, D. Appleton & Co. (1895)

Barbara Oberg. "New York State and the "Specie Crisis" of 1837" (PDF), Business and Economic History., 2nd Series, Vol. XIV (1985)

Lawrence H. Officer, "Gold Standard" EH.net (26 March 2008)

James Powell, A History of the Canadian Dollar (complete text online), Bank of Canada (2005)

Bruce Smith, "The Relationship Between Money and Prices" (PDF), Quarterly Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (Fall 2002)*

* In order to read, right click link and select "save link as," then open in PDF reader.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home