(

Part 1)

THE NIGHTWATCH

There are conflicting versions of the story, even among company publicists. In 1901, one Marius Hogrefe, a [draper? lawyer?] founded the Kjøbenhavn Frederiksberg Nattevagt (Copenhagen-Frederiksberg Nightwatch).

1 The nightwatch was a fairly commonplace business entity in Europe at the time, and similar organizations in Hälsingborgs (1934), London (1935), and elsewhere would become ancestors of AB Sercuritas and G4S, plc.

2 Securitas' own corporate website claims "Erik Philip-Sörensen founded Hälsingborgs Nattvak,"

which is unlikely. What is mentioned by all accounts of Securicor (London), Falck (Copenhagen), Securitas AB (Stockholm), and ISS A/S

(Copenhagen) is that they grew by absorbing very large numbers of nightwatch companies, in a process that was mostly completed by 1964.

(In this essay I frequently use company names anachronistically; ISS A/S adopted that name in 1973, while Securitas AB adopted its name in 1972. Securicor, plc, took that name in 1953, and no longer exists. Moreover, there are several companies in the Scandinavian/German-speaking countries that have "securitas" in their name, which are unrelated to the entity known as Securitas AB.)

A common theme is the Philip Sørensen name: the Kjøbenhavn Frederiksberg Nattevagt eventually became ISS A/S; Erik Philip-Sørensen was responsible for a wave of

nattvakt acquisitions in Sweden that latter became Securitas AB (initially an ISS A/S subsidiary, later bought out by the Philip-Sørensen family).

3 Later, Jørgen Philip-Sørensen moved to the UK in 1964 to establish Group 4, yet another security company. In 2000, Falck merged with Group 4; the Falck family involvement was long gone but the Philip Sørensen clan remained in control of the merged entity (G4F, plc). In 1983, Sven Sørensen sold his stake in Securitas AB to Skrinet and Cardo, and Jørgen did the same.

4 Cardo AB is a Swedish lock and armored door producer; Skrinet was an investment group. Both were later absorbed into Investment AB Latour.

The

nattvakt/

nattevagt businesses of Scandinavia had been funded by subscriptions for beneficiaries; households and businesses had paid the local nightwatch to protect their premises, but there was presumably spillovers. Copenhagen, in particular, first had a permanent (state-run)

nattevagt around 1783, and an English-style police force after 1863.

5 But ISS A/S's precursor, DFVS, was able to bundle security with a large number of other services,

viz., cleaning. In fact, in the case of DFVS (i.e., the future ISS A/S), even its prominent DDRS was pitched as an augmentation to its security services. DDRS was the public face of the company: single women, usually younger, using modern Swedish equipment (DDRS had a special agreement with Electrolux), maintaining cleanliness. Possibly--but this is conjecture--the larger DFVS, with its selective policing on behalf of private, wealthy clients suggested a disturbing violation of Scandinavian egalitarianism.

6

Click for larger image |

RESCUE CORPS TO RENTA-COP

Concurrent with the commercialization (?) and business consolidation of the

nattvakt/

nattevagt was the appearance of professional

Redningskorps. Unfortunately, I was unable to find out much about the history of the

Redningskorps besides the corporate histories for Falck.

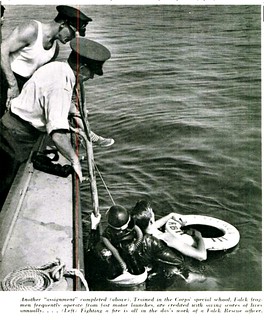

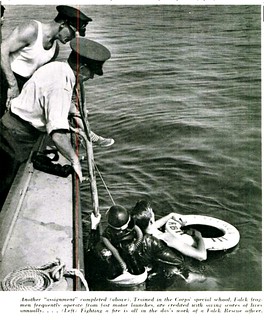

7 Basically, the

Redningskorps were similar to modern fire departments, with emergency rescue and repair services. Sophus Falck is claimed to have founded the

Redningskorpset for København og Frederiksberg (1906). Later, the by-subscription RKF changed its name to Falck, and by the late 1950s, covered the whole of Denmark with over 106 stations. Its fleet of motor ambulances--the earliest in Scandinavia, if not the world--accounted for 80% of medical transport in Denmark.

Initially, Falck's business consisted of fire salvage: rescuing valuable items from burning structures while fire crews fought the fire.

The business model included immediate assistance for everyone, with billing for nonsubscribers. Subscribers, presumably, paid less or nothing extra for service. The business grew rather slowly (Denmark is a tiny country, and it required about fifty years to saturate the country). By the time the Falck family sold the firm to Baltica Insurance (1988), it was probably the most respected firm in Denmark.

It's hard for an outsider to tell what the effect was on Falck. At the time, subscribers were mostly Danish, the firm was still quite small, and coverage of Falck in the business press was probably confined to Scandinavia. Baltica later sold a major stake in Falck, and in 1995, the firm was listed on the Copenhagen SE. By then, it had gone into empire building in a big way. It bought the Danish business of ISS, ISS Securitas (which Securitas AB bid for as well), plus several regional firms.

8

The share issue permitted Falck to finance a merger with the remaining Sorensen holding, Group 4. Thereafter, Falck was no longer separately traded; it would be listed on the stockmarket as G4S.

In the new entity, Falck had the advantage (institutionally) of not having family ownership; Lars Nørby Johansen had been brought in well after Baltica's purchase and partial divestment but had managed to secure himself there despite the absence of any loyal shareholder.

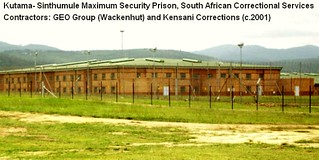

9 In contrast, Jørgen Philip Sørensen (who died in 2010) remained in the minor role of chairman of the board, still damaged by the many scandals Group 4 suffered during the first couple of years as a correctional contractor in the USA.

One of the reasons why rising productivity over the last twenty five years has not translated into rising wages is that firms consolidate to capture external spillovers,

i.e., market power over suppliers, consumers, employees, even financial markets and governments. This is expensive, and absorbs an immense amount of revenue. Firms respond, as did Falck, by cutting back personnel, reducing targets for customer satisfaction, and availing themselves of more advanced financial instruments. Efficiency methodologies sometimes make a difference, but the larger (

i.e., merged) firms don't seek efficiency so much as market power. Too much efficiency, after all, can reduce the systemic consequences of the firm's failure on affected governments, and cause them to become indifferent to the firm's comparative success.

Group 4 Falck soon after bought Wackenhut, the second largest US security firm (as well as its second largest private prison operator), Hashmira (the largest Israeli security firm), and Securicor.

10 The newly created entity today has 657,000 employees and ongoing scandals over high-profile contracts it has mismanaged, such as the 2012 London Olympics; still, its operations globally make all of that inconsequential: in the Global South, it is very successful.

BIG AND BIGGER

That leaves Securitas AB, the Danish-originated, Swedish-based firm where I left off above: the Sørensen clan dissolving its ties to the company, whence it became a part of Investment AB Latour, a financial vehicle for Gustav Douglas. Count Douglas is, according to

Forbes (

March 2012), the world's 418th richest person.

When I first began researching for this article, I had been startled to notice that Wackenhut was now the GEO Group, and it was owned by Group 4 Falck; then I noticed that, no, the GEO Group was now a tiny speck in the vastness that is G4S, plc. More amazing still was that the old core of G4S, Group 4, had been the London side of a family empire whose other side was Securitas AB of Stockholm; and that Securitas had gone through a second phase of international growth, snapping up Pinkerton, Burns Security, and Loomis Fargo (USA) and Reliance (UK)--entities I remembered as fearsome hired guns.

Now Securitas AB employed 309,000 employees in 50 countries. The two old halves of Philip Sørensen's empire employed over a million people, a majority of them guards of some time. Another piece--ISS A/S, once managed by Philip Sørensen and his son Erik--had 390,000 more. All three had grown with amazing speed to their present size. ISS A/S was privately held, G4S, plc, was institutionally owned (at least, the re-listed Falck part is), and Securitas AB was... one of 70 companies wholly owned by Investment AB Latour.

11

To be sure, not all of the firms are on the same order of magnitude as Securitas AB. And it's possible that in another year, G4S, plc, will partly unravel, Latour sell Securitas, and ISS be reduced to listing itself. But for now, the empire of the Sorensens is opaque at both ends.

UPDATE: Falck A/S was spun off from G4S, plc, in 2005 and sold to Nordic Capital Fund V and ATP Private Equity Partners. It continues to be mostly ambulance services, in seven countries of Europe. In April 2011, Nordic Capital sold its stake in Falck to the Lundbeck Foundation. Today, 57% is owned by Lundbeck and 20% by the Kirk Kristiansen Foundation (KIRKBI Invest A/S). KIRKBI's most famous holding is the LEGO Group (toys, entertainment) and Lunkbeck's most famous holding is the pharmaceutical company H. Lundbeck. All of these organizations are Danish.

12

ISS A/S, as I mentioned above, is also privately held. In 2008, a pair of private equity firms "took the company private," meaning they bought all the shares outstanding and delisted it: EQT Partners and Goldman Sachs Capital Management (GSCM). In 2012, the Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan (OTPP) invested $437 million and the Kirk Kristiansen Foundation (KIRKBI Invest A/S) invested $187 million in ISS A/S. Afterward, this investment was regarded as 25% of ISS A/S's equity, implying that the entire firm was worth $2.5 billion.

13

Notes

- "The ISS Story" (p.1) refers to founder Marius Hogrefe as a draper; Dahlgaard, Khanji, & Kristensen (2007) merely refer to "a lawyer"(p.288). Abrahamsen & Williamson (2010, p. 43) say Marius Hogrefe and Philip Sørensen. "The ISS Story" precludes this by claiming (p.2) that it was long after that the company was founded that Philip Sørensen was hired. Group 4, Securitas AB, and ISS A/S were all founded or managed by members of Philip Sørensen's family; Falck came under Philip Sørensen control after it merged with Group 4.

- "History: G4S can trace its roots back to 1935 in the UK, making 2010 its 75-year anniversary," corporate history of G4S, plc, hosted at G4S's website (accessed 27 Feb 2013).

[G4S]'s earliest roots in the UK appeared in 1935 when a former cabinet minister launched "Night Watch Services"--a modest enterprise with four bicycle-riding guards in old police uniforms. In 1951 it was renamed Securicor and it floated on the London Stock Exchange in 1971.

With respect to Securitas AB,

In 1934, Erik Philip-Sorensen brought the company into Sweden, buying Hälsingborgs Nattvakt, based in Helsingborg...

(From Jay P. Pederson, International directory of company histories, Volume 42, St. James Press (2001), p.336. I am not sure when or by whom, the original Swedish nattvakten were founded, but the ones mentioned are all for towns bordering the Øresund.

- "The family bought out the larger company in 1938,

taking full control of the Swedish Securitas (ISS maintained the Securitas name elsewhere). Sweden now became the family's primary activity." Jay P. Pederson (2001), p.166.

- Kemp Powers, "Still sore," Forbes (4 Jan 2002; accessed 27 Feb 2013). Powers was unable to reach Sven, who unilaterally decided to sell his 75% state in Securitas AB. Displeased, Jørgen felt he had no choice but to sell his 25%. At the time, Securitas was worth far more than Group 4. AB Latour notes on its history page that it absorbed Skrinet.

- For the original Copenhagen nightwatch corps, see Sven Håkon Rossel, A History of Danish Literature, University of Nebraska Press (1993), p.107. It was founded by Ole Rømer, who is most famous for determining that light had a finite speed. For the reorganization of the Copenhagen municipal police, see Lester B. Orfield, The Growth of Scandinavian Law, University of Pennsylvania Press for Temple University Publications (1953), p.37.

- I became aware of collaboration between DDRS and Electrolux via "The ISS Story" (PDF), but that article says it began with a 1976 plan to acquire and operate cleaning companies (globally?), p.5. According to Electrolux's 1971 annual report (PDF), p.13, the two companies had shared ownership of ASAB for several years.

My conjecture about the marketing strategies employed by DDRS/DFVS is drawn from reading between the lines of "The ISS Story." The author seems utterly befuddled by some unnamed storm that broke around DDRS in the early 1970s, leading to it changing its name and shifting its focus to the Global South. Unfortunately, Dahlgaard, Khanji, & Kristensen (2010) shed no light on the subject.

- My main source for the history of Falck prior to 1961 is Robert Rigby, "Denmark's Remarkable Rescue Corps," The Rotarian (Sept 1961 issue), p.14.

- Skaarup (2011), p.9

- Schmidt, Adler, Weering (2003), p.18. Schmidt, et al., are extremely favorable in their discussion of Falck & Group 4 management; arguably Schmidt had an interest in depicting another private security firm management team as positively as possible. According to the Danish Wikipedia entry for Johansen, he became CEO in 1998, not 1988. In an interview he tells Schmidt, et al. that that he has "been in the business for 15 years," implying perhaps that he spent ten years at Falck before becoming CEO.

- M&A activity after Group 4 Falck's creation in 2000 has been heavily covered in the Guardian Online. For the Wackenhut purchase, see "Denmark-Based Security Firm Group 4 Falck/Wackenhut Assailed by Transatlantic Union Alliance for Poor Practices in United States," PR Wire (9 October 2003). Regarding Hashmira, see Peter Lagerquist and Jonathan Steele, "Group 4 security firm pulls guards out of West Bank," The Guardian Online (22 Oct 2002). For the new role of the firm once known as Falck, see "A fate worse than prison," The Guardian Online (11 Nov 2002). Perhaps most unfortunately for Falck, Wackenhut's extraordinary notoriety comes from the behavior of one of its subsidiaries, the Australasian Correctional Management (based in Australia). But Wackenhut has plenty to be embarrassed about on its own, which may explain why it changed its name the next year to GEO Group (All stories accessed 27 Feb 2013).

- Re: ISS A/S, see: "Company Overview of ISS A/S," Businessweek (accessed 27 Feb 2013); Re: G4S, plc, see Skaarup (2011), p.10; re: Securitas AB, see Latour: Holdings (website accessesed 27 Feb 2013).

- John Acher & Ole Mikkelsen, "PE-Backed Falck Explores IPO," Reuters (22 April 2010). For H. Lundbeck A/S's foundation buying much of Falck from Nordic Capital, see Will Waterman, "Nordic Capital exits Falck," Reuters (28 April 2011). On the current composition of Falck's ownership, see "About Falck: Owners," official webpage of Falck A/S.

- For the delisting of ISS A/S, see "PurusCo A/S completes the recommended tender offer for shares of ISS A/S" press release hosted at EQT Partner's website (9 May 2005; accessed 28 Feb 2013). For the details of the later buy-in by OTPP and KIRKBI Invest A/S, see ISS A/S's 2012 Annual Report (PDF), p. 4. PurusCo was a Danish entity created by EQT and Goldman Sachs as a vehicle for the buyout. As always, currencies are converted at the approximate date of the announcement. In Oct 2011, G4S, plc, made an abortive bid to buy ISS from its owners; it offered £5.2 billion, or $8.1 billion ("EQT Partners and GS Capital Partners exit ISS," Invest IQ, 17 October 2011).

Sources and Additional Reading

Rita Abrahamsen & Michael C. Williamson,

Security Beyond the State: Private Security in International Politics, Cambridge University Press (2010)

"

The ISS Story" (PDF), anonymous, hosted by ISS website (no date; accessed 27 Feb 2013)

Jens J. Dahlgaard, Ghopal K. Khanji, & Kai Kristensen,

Fundamentals of Total Quality Management, Psychology Press, (2007)

Kemp Powers, "

Still sore,"

Forbes (4 Jan 2002; accessed 27 Feb 2013). About the Philip Sørensen clan.

Robert Rigby, "Denmark's Remarkable Rescue Corps,"

The Rotarian (Sept 1961 issue), p.14.

Waldemar Schmidt, Gordon Adler, Els van Weering,

Winning at Service: Lessons from Service Leaders, 1st Edition, Wiley (2003);

note one author, Waldemar Schmidt, is a former CEO of ISS (whose main competitor, G4S, plc, is profiled in this book).

Thomas Skaarup , "Strategic analysis and Valuation of Falck A/S" (PDF) Masters Thesis, Copenhagen Business School (Nov 2011)

Labels: anthropology, governance, social research