The Command Economy

"Command Economy" is a term of art usually confined to the economies of Communist nations. The last two plausible examples might be North Korea and Cuba, although it's often pointed out that in both societies, central planning broke down long ago. Other Communist systems, such as the CMEA bloc (Moscow-aligned), China, Vietnam, Yugoslavia, and Albania, each had various strategies for coping with the impossibility of centralized command.

An economy which relies wholly on the movements of price to adjust volumes of output is usually known as a "market economy," and occasionally as "the price system." The latter term was used often by critics of market economies during the 1920's and '30's (e.g., The Technocracy Movement, Thorstein Veblen).

The Nature of the Problem

Every individual is continually exerting himself to find out theIt's long been a trivial observation that large numbers of people, pursuing their "best interests," and informed mainly by the prices of things, can plan an economy more efficiently or successfully than can any central agent. I put "best interests" in quotes because the term is used here in a specialized sense, to mean, directed by the need to maximize benefits given one's initial endowments of time and property. Economics emerged as a system of philosophical deduction, with some empirical methods thrown in, based on the concept that the natural response of producers and consumers in the market was to bring the supply of all commodities in alignment with demand using nothing but signals of price.

most advantageous employment for whatever capital he can command.

It is his own advantage, indeed, and not that of the society,

which he has in view. But the study of his own advantage

naturally, or rather necessarily, leads him to prefer that

employment which is most advantageous to the society.

The Wealth of Nations, IV.ii, Adam Smith

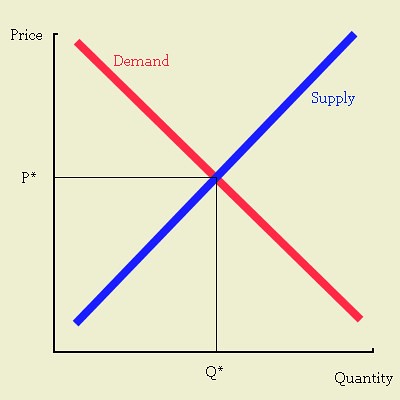

Usually, in basic courses on economics, students are presented a chart with two intersecting lines. Q* and P* represent the equilibrium price and quantity. If a seller tries to sell her output for more than P*, no one will buy it—they'll go elsewhere. So P* is the prevailing price. For ease of exposition, the blue line shows the correspondence between price and quantity supplied; the red shows the correspondence between price and quantity demanded.

In order to establish what P* and Q* ought to be for a number of goods, Walras argued, it was necessary to know the utility function for the general public; the quantity of capital services available to the economy; and the production function available to the economy for each good. Writing in 1870, Walras had hoped to simplify the analysis of his system by treating capital as a stream of potential services. In order to solve for the price of P* and Q*, in the illustration above (a partial equilibrium analysis) there existed a supply equation S = S(P), and another demand function D = D(p). So

and finding a solution is actually a fairly easy problem in algebra. But for a general equilibrium, there were many equations of multiple variables required to solve for multiple unknowns: the supply of any particular good was a function of all the capital inputs, plus the cost of intermediate commodities, plus some function of labor; while the quantity demanded of that good was a function of income and the price of all other goods.

Because it was inconceivable that humans would ever be able to solve an equation that realistically described these relationships, economists have mostly confined themselves to partial equilibrium analysis—in other words, holding nearly everything constant, and changing a tiny number of variable inputs. However, in the 1950's and '60's, with the work of Kenneth Arrow, Gerrard Debreu, and Piero Sraffa (PDF), it was now considered possible to examine alternative descriptions of general equilibrium mathematically, and make inferences about the results applicable to our actually-existing economy. Additional elements were introduced: economists such as John Muth, inter alia, introduced the role of the stochastic [random] technology shock in general equilibrium analysis. This was the foundation of Real Business Cycle (RBC) theory, which was coupled with another by-product of revived general equilibrium analysis known as Rational Expectations (RE). The RE/RBC model has evolved substantially since its initial introduction, and today is known as stochastic dynamic general equilibrium (SDGE) theory.

A command economy, in theory, could largely replicate the role of prices in creating an equilibrium in which all resources were utilized. Here, however, the utility function would be replaced by some new system of equations. The new system of equations could presumably allow for a sudden and drastic shift of production, accompanied by some catastrophic loss of capital services (say, as a result of either peak oil or a collapse of the US dollar against that of our trading partners). In the past it has been assumed that true command economies, in which managers calculated an optimal output of each commodity based on existing resources, would be technically static; this is not necessarily true. On the contrary, technical innovations in production or goodness of fit could indeed be introduced into the planning equations as soon as these innovations had been tested.

It also needs to be pointed out that command economies need not be centrally planned. Again, because of the experience with CMEA economies (discussed below), people assumed that command economies were necessarily planned from the capital city of the hegemonic power. That was in fact an erroneous impression based on Cold War ideology. A command economy could conceivably consist of many autonomous planning nodes which share information about planned outputs; the outputs, in turn, would supply the necessary variables for each other's general equilibrium. Difficulties might arise, however, when planning nodes had disputes over jurisdiction—say, if there were a hierarchy of planning nodes, with one for a particular state, subdivided into county nodes with different productive functions.

This is not to endorse any such scheme. First, if I did endorse such a scheme, I would be dismissed as a crank—no one would have the slightest interest in the idea. Second, there are many obvious problems with it.

- The data processing overhead would be huge; detailed information on the potential output of all capital equipment would have to be available at all times; additionally, some clearing house of data on planned usage of each commodity or semi-finished good, combined with reliable estimates of output, would have to be available to all planning nodes.

- A lot of the actual judgments required in real-world planning are subjective: morale of the labor force, elasticities of quality, the consequences of plan failures or delays, and so on.

- Most importantly, humans would have perverse incentives to hoard resources (causing plan failure, then a crisis-shortage and opportunities to profiteer); the most talented would tend to be punished by a system that was intent on stability and reliability; the system as described expects consistently average performance, rather than the actual norm of brilliance mixed with appalling ineptitude.

For the record, the enterprise resource planning (ERP) concept in software was created with the ultimate goal of allowing a company to integrate all information available to any of its departments for making decisions. My brush with the concept was as a purchasing agent for a large US-based airline. I read that an ultimate goal was that any information that reached the database anywhere could be used to make decisions everywhere. For example, when the Apollo booking system (which covers all airlines) registered another ticket purchase for a flight from LAX to SHA, that ticket purchase could be used to register information about future traffic patterns in that particular corridor, if the purchase was profitable (or would have been profitable) for our airline; if from the airline, the purchase could be used to register the increased load on airplanes servicing that route, and the increased need for staff at those respective terminals. Such data might contribute to information about replacement interior panels, increased hours of service by staff in some departments, and how much additional coffee to buy for the company canteens.

The record suggests that ERP's are still a very immature technology, and may never succeed in actually integrating information perfectly; but the interesting thing is that corporations remain, as they always have been, the test-bed for a lot of the technology of command economies.

Communist Command Economies (references)

It may be surprising to learn that the Communist countries were not true command economies. In one sense, they were definitely command economies, since the political leadership was authorized to administer production by decree. However, the political leadership lacked the technology required to either make accurate judgments of economic activity, or make its commands stand. Only in certain pockets of the Communist world did conditions of command truly prevail.

The Communist world, of course, was actually quite heterogeneous. The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA or Comecon) comprised the USSR and other Warsaw Pact countries; Mongolia, Cuba, and Vietnam. Forms of membership were extended to all Moscow-allied countries, such as Iraq and Afghanistan, and to Yugoslavia (after 1964). However, because of the overriding importance of the KGB in the Soviet system, the value of regimes' intelligence or military collaboration with Moscow tended to trump anything else. Cuba, for example, was extremely valuable and hence received immense assistance; South Yemen, conversely, had entered the alliance late (1970) and was known to be extremely unstable. CMEA served more as a useful expression than an actual component of the Communist command economy.

Still, Czechoslovakia and East Germany were exceptionally integrated components of CMEA. This was due in part to an ironic, but understandable, contrast between CMEA and its neighbor, the European Economic Community (EEC). First, the EEC was created by treaty with limited, but definite, supranational authority; CMEA was a shadow organization whose importance was eclipsed by the strategic considerations of the KGB. So while the EEC could make its decisions stick, CMEA could not. Second, despite being a group of market economies, the EEC was a sort of idealistic trust; it had a mandate to achieve greater solidarity through economic convergence. Hence, its policy of stimulating industrial development in Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and Greece (with considerable success). CMEA, in contrast, had insisted that there was no hierarchy in socialist economies; its organs wanted to stimulate the development of industry in northern members, where it was strongest, and have the southern members focus on services or agriculture. Under the Soviet style of command economy, this made sense, but it alienated the southern members. Again, strategy trumped economy and CMEA was sidelined.

However, even the most technically or ideologically advanced of the CMEA bloc were unable to implement genuine central planning. While the various organs of the CMEA produced an immense and increasing number of detailed economic decrees, these lacked the appropriate semantics of economic management. Rather than map the inputs and outputs to a system of linear equations, the most ambitious central planners used huge flow charts to plot the flow of commodities through the system. While unmanageably ambitious as plans, they were not fine-grained enough for firms to follow directly, so a shadow system of planning evolved instead. As early as the 1926 Scissors Crisis, the Soviet planners had relied not on a drastic revision of the structure of production, but an evolution projected forward from the pre-revolutionary economy. In other words, the Soviets planned for the 1932 economy to be a set of multiples of the 1914 economy; industry was essentially built with heavy subsidies from agriculture, and heavy industry from light industry. There were discontinuities, such as the collectivization of agriculture, the "coal campaign," the "battle of steel," and so on, but by the 1950's everything was geared towards incremental expansion. Waste and inflation were built into the system because accurate estimates of necessary inputs were impossible, but real planning was carried out at the enterprise level. Decrees were fulfilled by managers becoming brokers of phantom material or hoarded output; otherwise, the role of the central planner was to catch up with reality, not construct it.

For this reason, the Soviet system was known as "state capitalism" by critics, who noticed that was really managed by allocations of capital, not by planning. Social objectives were met by making them easier to fulfill; only military needs were non-negotiable.

Corporate Command Economies (references)

It's a bit harsh to liken Western firms to Soviet ones, but in many cases they are similarly clueless and unresponsive. Detailed accounts of Nazi economic policies (Guerin, 1939) within Germany reflect a determination to leave enterprise control mostly intact; executives of German enterprise mostly did not experience any sort of difficulties with Nazi rule. There was some grumbling about the immense debt that the Nazi regime ran up, but mostly the Nazis gladly left the management with increased control over their own enterprises. Following prevailing wisdom of the day, there was a plan to stimulate the economy by pushing prices upward through cartels. During the Great Depression in Germany (1924-1930), the Weimar Republic had bailed out companies by buying their stock above market. In many cases, the Nazi regime reversed nationalization of banks or firms by giving the management stock it had sold to the Weimar Republic (Guerin, p.211).

A particularly astonishing decree of July 1933 empowered the Minister of the Economy to prohibit the increase of output of existing enterprises or the founding of new ones (Guerin, p.214). The Minister was empowered to peg the output of plants to desired (low) levels. Also, he was empowered (instructed) to carry out the wishes of existing cartels to enforce compliance with cartel price and output decisions, particularly with respect to non-members. In this sense, the Nazi regime incorporated a command economy, in which management within each industrial sector issued decrees.

The Nazi regime was an extraordinary case of capitalist management establishing national command. However, during much of its evolution, enterprise in the USA was largely focused on mastering techniques of concentration and centralization. This took the form of industrial methodologies such as Taylorism, in which the old methods of factory-level management were replaced with central headquarters issuing directives to far-flung plants worldwide. In some cases, it was congressional policy to resist consolidation through anti-trust laws (Sherman Anti-Trust Act) or separation of sectors (Glass-Steagall Banking Act) or regional subdivision (McFadden Act). After 1953, this trend was reversed, and Congressional influence tended to favor domestic industry with restricts on capital exports. Around the 1970's, that ended as most capital exports were occurring within firms (from domestic to foreign branches).

The command aspects of US firms have tended to distinguish them from the more generally federal character of foreign enterprise. Large European or Japanese companies have only recently tended to meld internally; many of them were essentially cartels with a single firm name and integrated accounting system. While executives of the modern corporation would bristle to hear themselves likened to Soviet commissars, it must be noted that the technical obstacles and failings were often quite similar.

ADDITIONAL READING & SOURCES:

Communist Command Economies: most available information on Communist command economies can be found in the 4-volume work by Edward H. Carr, Foundations of a Planned Economy (1969), and from Christopher Howe, The Foundations of the Chinese Planned Economy (1990). The latter book is a documentary survey which can be supplemented by the very useful anthology Communist China 1955-1959: Policy Documents with Analysis (Harvard University Press, 1965). On the economic policies of the Nazis, there is Daniel Guerin, Fascism and Big Business (1939/63), which includes a very detailed documentation of the decrees—pp.208-252; also, Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1949/64); but the latter is not very focused on economics or management.

Corporate Command Economies (added 23 August 2008): Adam Tooze, The Wages of Destruction, Penguin (2008) describes in considerable detail the operations of the Nazi economy, forcing me to reassess drastically the relationship between party and industry in the Third Reich. The Nazi economy was in continuous flux towards a command economy, and by the time Albert Speer succeeded Fritz Todt as minister of armaments production (a position just below that of the Führer), in '42, the Third Reich was categorically a command economy. Interestingly, Tooze cites diary entries by Nazi officials lamenting that the USSR was a much more compelling example of a command economy; evidently, the military leadership tended to regard their own society as comparatively free, especially in the economic sphere. Nevertheless, the Reich remained emphatically capitalist.

Veblen/Price System: I have mentioned Thorstein Veblen's critique of what he referred to as the price system, The Engineers and the Price System (PDF-1921). Veblen was writing in the wake of the most intense depression of North American history, the post-WW1 depression that lasted for 18 months. The more famous Great Depression (1929-1939) was much longer, but less severe. For information on the Technocracy Movement, there is an excellent site by Prof. Thayer Watkins that describes the history of this curious political association.

Leon Walras: author of Elements of Pure Economics (1870). Walras integrated many then-new concepts in classical economics, such as the utility theory of value (and with it, the utility function) and the concept of general equilibrium. Between 1870 and 1930, this was orthodoxy in economics, and it has become orthodox again (since 1976) , with some minor adjustments. Here is a fairly easy-to-grasp introduction to the concept of Walrasian General Equilibrium (PDF). Walras was not supportive of a command economy; however, some of his less famous and later works tended to suggest an accommodation with socialist ideas (Roger Koppl, "The Walras Paradox" 1995). This has not interfered with his immense reputation among conservative orthodox economists.

Rational Expectations has been the topic of many books. The Rational Expectations Revolution (edited by Preston Miller; MIT Press, 1994) was one of my econ textbooks; it includes many of the crucial polemical articles written in the early years of the RE/RBC "revolution" in economics. Another book, recently revised, includes a later assessment of the RE/RBC revolution: Rational Expectations, 2nd Edition (Steven M. Sheffrin, Cambridge, 1996). Assessing Rational Expectations (Roger Guesnerie, 2001, MIT) includes analytical scrutiny of the variations of RE, reflecting the fact that, by the end of the 1990's, RE was less of a theory than a methodology.

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP): Christopher Koch, "ABC: An Introduction to ERP" (2007);

Labels: economics, enterprise resource planning, ERP, history, planning, semantics

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home