Tradable Streams

Every time the topic of high commodity prices comes up, there's a lot of talk about Enron. Can speculation drive up the prices of traded commodities? Of course, Enron proves it. That's the commonsense answer, and I think it would be a good idea to address this in a dedicated post on the subject.

The Story of Enron

Enron was a very large energy company created by a flurry of mergers and acquisitions in the early 1980's. The core firm was InterNorth, a holding company created in 1979 to provide an additional layer of protection from the risks of a rapidly expanding subsidiary, Northern Natural Gas Company. The purpose of Northern Natural Gas was to build and operate 103,000 Km of PNG pipeline connecting Texas and the Great Lakes region. InterNorth acquired a natural gas supplier, Houston Natural Gas, and changed its name to Enron (1985). The following year Ken Lay, took over at the company, and relocated it to Houston.1

Enron remained almost exclusively a PNG supplier and pipeline operator until 1998. That year it attempted to diversify into water; they acquired Wessex Water, turned it into Azurix, and lost about $2 billion trying to turn water into a lucrative business.2 Enron then turned to broadband, partnering with Sun Microsystems to dive into the internet bubble. That, too, was a hugely costly failure that was not wrapped up until November 2001. But Enron's real business was trading in streams.

Streams Explained

A stream (in this sense) is a supply of a benefit that has to be continuous through time. An example of this is electricity. Electricity, for the end user, is something that has to be available at all times. Hence, when streams are commoditized and traded, they are fundamentally different from other commodities. First, there is no possibility of an inventory; electricity cannot be stored. It has to be continuously available to be useful. This means that, as a tradable thing, streams must necessarily incorporate a period during which they are supplied.

Someone might point out that the things I refer to as "flows," viz., crude oil, iron ore, gold, pork bellies, rolled steel, and the like, have active futures markets. Futures contracts specify not only the amount and quality of the commodity to be delivered, but also the date of delivery. But those are derivatives, not the underlying good. Second, a future contract to deliver a load of a particular commodity on a particular day is not comparable to a contract to deliver a stream of service over a period of time. The exact time period of the service is an inherent and permanent feature of the thing being sold.

Examples of Streams

The most obvious examples of tradable streams are

- pressurized natural gas (PNG);

- electricity;

- water/wastewater;

- broadband internet connectivity;

- long distance telephone service;

- insurance.

Problems with Trading Streams

As we shall see, this makes trade in streams inherently much more complicated than trade in flows.

The first reason is that packaging a stream (as opposed to an item like an ingot of steel) is likely to sharply impinge on the value or character of that stream. For example, for industrial applications, a kilowatt-hour is not a generic thing at all; often major commercial consumers of electric power require a premium vendor who can ensure no spikes, extra support, and so on. While it's possible to specify different grades of stream, or even unbundle those services and trade them as separate steams, this defeats the point of premium service since the consumer has to essentially replicate the administrative abilities of the premium supplier.

Second, markets don't clear in the same way when the commodity is time-specific. Let me explain again: other commodities can be traded as future contracts, for delivery of a specific amount, quantity, and quality by a specific point in time; a stream is for something that exists only during a period of time, namely, the period during which it is actually used.

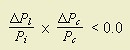

The market price of a thing represents the opportunity cost to the supplier of actually supplying that good to the person paying the price. In other words, commodities have prices because they are scarce, which is to say that there are alternative uses for them. Our market economy uses prices to ration commodities to those who can pay the most for them. However, as the time approaches when the stream bid upon is to be delivered, the price can become highly volatile.3 The total number of buyers and sellers shrinks very fast, which tends to make any "equilibrium price" very unstable. Essentially, basic economic theory gives way to the arcana of game theory and multiple equilibria. The result, at best, is a much more demanding regulatory environment; at worst, unacceptable disruptions in the system of energy supply; and in between, a permanently higher cost (if not price!) of the stream itself.

Part of the problem, naturally, is that both buyer and seller have a gun to the other's head. Trading in streams, in practice, typically involves transactions that take place literally minutes before delivery of the stream for the relevant time period. Since it's not really practical for smaller players to engage in games of "chicken," this restricts stream trading to very large customers.

This doesn't mean the concept is a failure. It does mean that the system only works when it's tightly controlled, as in Western Europe.

_________________________________________

1 Enron does have an extremely interesting history, especially since it consisted of a merger of several older firms. Bryce (2002, see below) emphasizes Houston Natural Gas (HNG) Co. as the core firm, as well as the peculiarities of Houston's business culture. However, Enron appears to have always been something of a bungling conspiracy of its components, rather than an organically unified entity.

2 When Bryce wrote Pipe Dreams, Enron had tried and failed to displace Vivendi (Compagnie Générale des Eaux) and Suez, the two French companies that dominate the market worldwide. As Bryce's book came out, it depicted Vivendi as the seasoned victor of its clash with Enron, which it was in 2000, when Azurix imploded. Nevertheless, Vivendi suffered a financial meltdown at the time of publication, as a result of Jean-Marie Messier's spectacular joyride at the helm (Time). Vivendi's water business is now Veolia Environment.

Suez is still in business; it dates back to the 1850's, although it had taken its current name in 1999 after a merger; its water operations are named "Ondeo," which makes for a much easier Google search. Suez is about to be acquired by Gaz de France (Forbes).

3 An exception to this is Nord Pool, where the balance from the spot market is maintained until the actual, physical delivery takes place under the regulating power market in Norway. Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Germany are also members of Nord Pool. Another energy trading regime exists in the UK.

_________________________________________

SOURCES & ADDITIONAL READING

- PBS: The Rise and Fall of Enron

- "Dueling Lawsuits in Enron – The Complaints in the Northern Natural Gas Dispute" (PDF) Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP

- "Blind Faith: How Deregulation and Enron’s Influence Over Government Looted Billions from Americans" (PDF), Public Citizen (Dec 2001)

- Robert Bryce, Pipe Dreams: Greed, Ego, & the Death of Enron, PublicAffairs/Perseus Books (2002)

Labels: economics, statistics